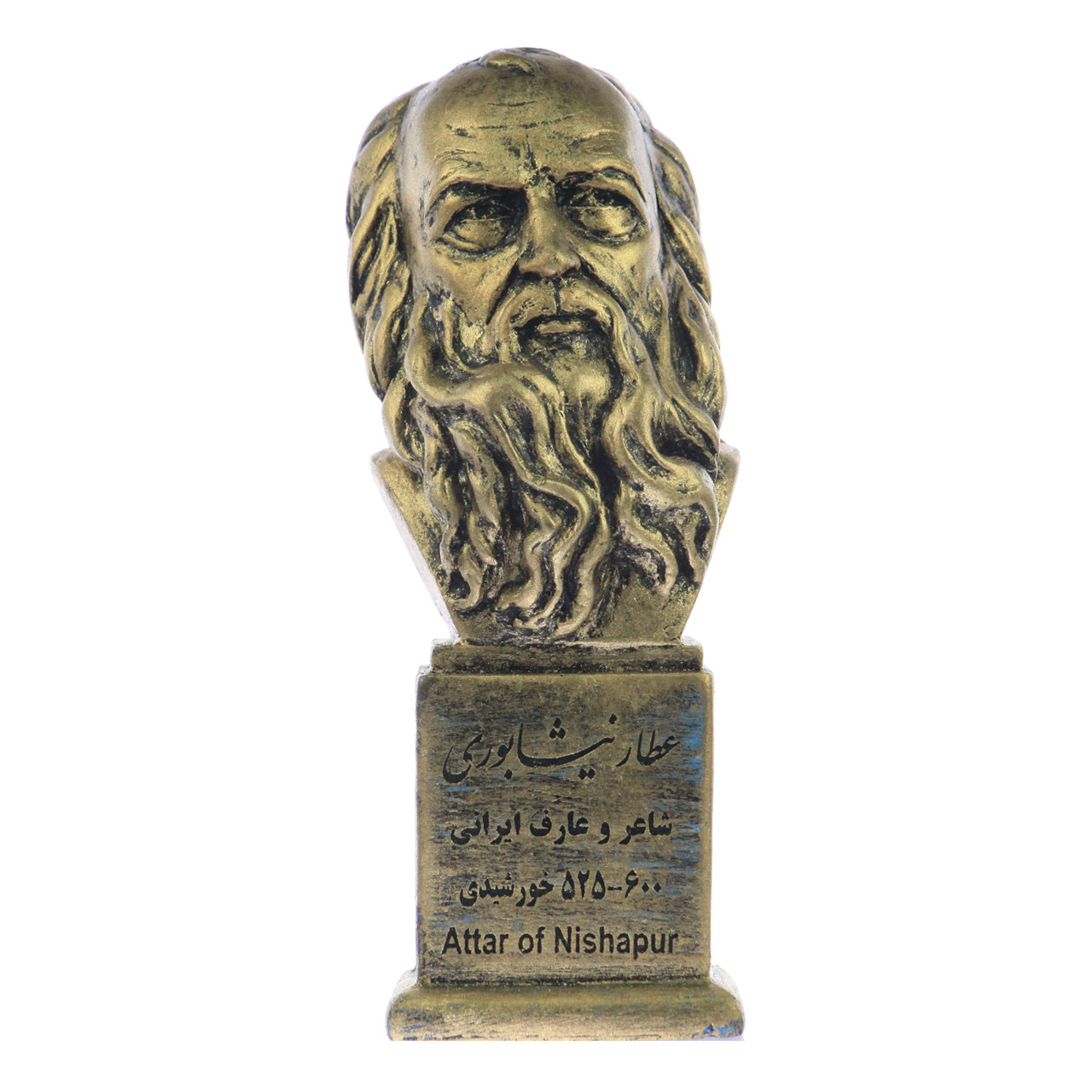

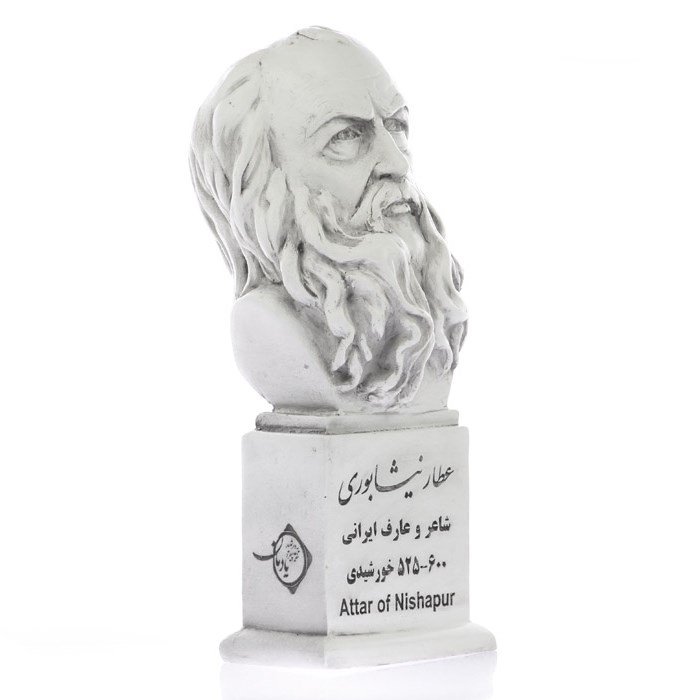

Biography

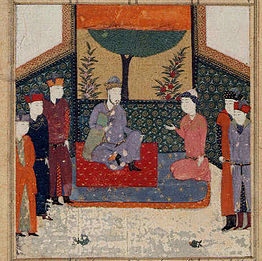

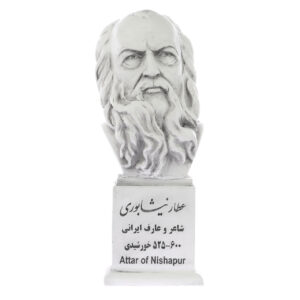

Information about Attar’s life is rare and scarce. He is mentioned by only two of his contemporaries, `Awfi and Tusi. However, all sources confirm that he was from Nishapur, a major city of medieval Khorasan (now located in the northeast of Iran), and according to `Awfi, he was a poet of the Seljuq period.

According to Reinert: It seems that he was not well known as a poet in his own lifetime, except at his home town, and his greatness as a mystic, a poet, and a master of narrative was not discovered until the 15th century. At the same time, the mystic Persian poet Rumi has mentioned: “Attar was the spirit, Sanai his eyes twain, And in time thereafter, Came we in their train” and mentions in another poem:

Attar traveled through all the seven cities of love

While I am only at the bend of the first alley..

`Attar was probably the son of a prosperous chemist, receiving an excellent education in various fields. While his works say little else about his life, they tell us that he practiced the profession of pharmacy and personally attended to a very large number of customers. The people he helped in the pharmacy used to confide their troubles in `Attar and this affected him deeply. Eventually, he abandoned his pharmacy store and traveled widely – to Baghdad, Basra, Kufa, Mecca, Medina, Damascus, Khwarizm, Turkistan, and India, meeting with Sufi Shaykhs – and returned promoting Sufi ideas. Attar was a Sunni Muslim.

From childhood onward Attar, encouraged by his father, was interested in the Sufis and their sayings and way of life, and regarded their saints as his spiritual guides. At the age of 78, Attar died a violent death in the massacre which the Mongols inflicted on Nishapur in April 1221. Today, his mausoleum is located in Nishapur. It was built by Ali-Shir Nava’i in the 16th century and later on underwent a total renovation during the rule of Reza Shah in 1940.

Teachings

The thoughts depicted in `Attar’s works reflects the whole evolution of the Sufi movement. The starting point is the idea that the body-bound soul’s awaited release and return to its source in the other world can be experienced during the present life in mystic union attainable through inward purification. In explaining his thoughts, ‘Attar uses material not only from specifically Sufi sources but also from older ascetic legacies. Although his heroes are for the most part Sufis and ascetics, he also introduces stories from historical chronicles, collections of anecdotes, and all types of high-esteemed literature. His talent for perception of deeper meanings behind outward appearances enables him to turn details of everyday life into illustrations of his thoughts. The idiosyncrasy of `Attar’s presentations invalidates his works as sources for study of the historical persons whom he introduces. As sources on the hagiology and phenomenology of Sufism, however, his works have immense value.

Judging from `Attar’s writings, he approached the available Aristotelian heritage with skepticism and dislike. He did not seem to want to reveal the secrets of nature. This is particularly remarkable in the case of medicine, which fell well within the scope of his professional expertise as pharmacist. He obviously had no motive for sharing his expert knowledge in the manner customary among court panegyrists, whose type of poetry he despised and never practiced. Such knowledge is only brought into his works in contexts where the theme of a story touches on a branch of the natural sciences.

Poetry

According to Edward G. Browne, Attar as well as Rumi and Sana’i, were Sunni as evident from the fact that their poetry abounds with praise for the first two caliphs Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattāb – who are detested by Shia mysticism. According to Annemarie Schimmel, the tendency among Shia authors to include leading mystical poets such as Rumi and Attar among their own ranks, became stronger after the introduction of Twelver Shia as the state religion in the Safavid Empire in 1501.

In the introductions of Mukhtār-Nāma (مختارنامه) and Khusraw-Nāma (خسرونامه), Attar lists the titles of further products of his pen:

- Dīwān (دیوان)

- Asrār-Nāma (اسرارنامه)

- Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr (منطق الطیر), also known as Maqāmāt-uṭ-Ṭuyūr (مقامات الطیور)

- Muṣībat-Nāma (مصیبتنامه)

- Ilāhī-Nāma (الهینامه)

- Jawāhir-Nāma (جواهرنامه)

- Šarḥ al-Qalb (شرح القلب)I

He also states, in the introduction of the Mukhtār-Nāma, that he destroyed the Jawāhir-Nāma’ and the Šarḥ al-Qalb with his own hand.

Although the contemporary sources confirm only `Attar’s authorship of the Dīwān and the Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr, there are no grounds for doubting the authenticity of the Mukhtār-Nāma and Khusraw-Nāma and their prefaces. One work is missing from these lists, namely the Tadhkirat-ul-Awliyā, which was probably omitted because it is a prose work; its attribution to `Attar is scarcely open to question. In its introduction `Attar mentions three other works of his, including one entitled Šarḥ al-Qalb, presumably the same that he destroyed. The nature of the other two, entitled Kašf al-Asrār (کشف الاسرار) and Maʿrifat al-Nafs (معرفت النفس), remains unknown.

Candle Holder

Candle Holder Coasters

Coasters Jewelry Box

Jewelry Box

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.